He gets

around London on a 550 c.c. Kawasaki Zephyr motorbike. A small plot of land

in North East Brazil, in the state of Bahia, also claims his attention. He

was there last summer to clear the undergrowth around the cashew trees and

coconut palms. Back in London, he has tropicalised his corner of a Council

housing estate. The gloomy brick is painted warm colours around his front

door and cage-birds sing inside. There is room for a barbecue in a recess

of the communal balcony, and when he cooks on it he invites his neighbours

round. From the same balcony a stand of majestic trees is visible, the remnants

of a nearby prison grounds.

Is it

too personalised to begin writing about Giacomo Picca’s art works in

this way? Somehow, to begin with a cool, impersonal tone seems inadequate

because Giacomo Picca himself gives the impression of someone on a journey,

and he speaks about his work in a similar, personal, way. He originally trained

as an engineer. He worked on several major building projects in São

Paulo but was outraged by the way the workers were treated in the Brazilian

building industry ("like another race ….."). He came to Europe

looking for an egalitarian society. No doubt he is still looking ……

But after settling in England in 1990 he enrolled in art school. He went first

to Chelsea, then Wimbledon, and completed his MA at Goldsmiths in 2000.

Confrontation with art, and the history of art, inevitably throws personal experience into a new light. The subjective is brought into relationship with the objective, material fact of the work of art. In a statement disarmingly entitled "This is What it is", Giacomo Picca has reflected on the relationship between the work of art which "exists because of itself", and the mutability of the individual life journey. In particular his move from one culture to another sharpened the riddle of the connection between the directly-felt and the historically-constructed, in the workings of our consciousness. "We all walk through a space somewhere between our experience and stories told to us of experience …. Through my own being – my psycho-geography – through my journey I have found that we inhabit many different spaces: there are shared spaces and universal images that we share; there are spaces created by cultures and societies whose images speak closely only to some of us."

It is

as if, in his art, Giacomo went in search of a sign that would be universal,

understandable in any culture, while acknowledging that the ‘factivity’

of the art object is actually the province of illusion.

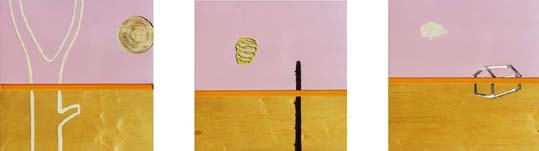

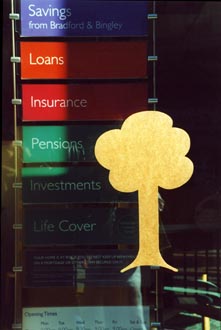

Hence his title for this exhibition. "Trees for the Wood" – a playful reversal of the famous English proverb. The confusion is apt because in these ‘paintings’ wood is the pictorial surface, the material and the subject-matter. In the original proverb, "not to see the wood for the trees" means that you are so stuck in the particular that you cannot get a view of the general, the whole. But this ‘general’ is exactly what Giacomo seeks by means of his attention to the particular, the wood. ‘Wood’ becomes ‘tree’ becomes ‘wood’, as a universal symbol.

There

is an innocence about his trees. They remind me of the early period of modernism

when artists were seeking simplified signs that, it was felt, anyone could

understand, transcultural images that could contribute to a universal visual

language of communication. The example of children’s art partly inspired

this search which had a radical, subversive energy at the time (remember Picasso’s

remark: "It was easy for me to draw like Raphael but I had to learn to

draw like a child"). There was also a practical need for such languages.

Electrical circuitry, statistical analysis, molecular structure, mapping,

‘finding your way’, and so on – these required internationally

standardised sing-languages (one of the earliest and most ambitious was the

Isotype system of the 1920s designed by Otto Neurath). There was a convergence

between the visual culture of science and art which was perhaps not fully

perceived at the time.

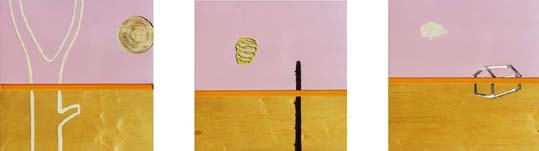

If this could be described as a ‘classic’ period of his work, Giacomo has recently moved into the romantic, with a series of works based on the landscapes of Caspar David Freidrich. And the constructive, architectural role that the lean, winter-tree image (discretely ithyphallic, it may be noted) played in the earlier works has now become something more indeterminate and ambivalent. Basing himself in landscape as a powerful representational configuration, deeply lodged in the psyche, the new work conducts an unexpected transformation of its materials. This proceeds on three levels, three surfaces: the given unpainted wood grain as a transcription of graphic energy, the landscape image as conventionalised painted signs, and, by the artist’s scraping away at the layers of plywood, the discovery of a chaotic, organic, a kind of protoplasmic material world below the surface. An element of violence is involved in revealing it, which contrasts strangely with the sublime vista of nature.

While

tautology and irony are a strong component of Giacomo Picca’s language,

they serve a sincere vision, a form of honesty. His reference to Caspar David

Freidrich suggests a desire to reconfigure the German romantic’s transcendental

poetry with the materials of "our world of design, DIY, media and advertising".

His ‘wood’ is not idealised but already acculturated at a popular

level. And from Giacomo’s own assessment of his dialogue with recent

art trends, an egalitarian, communicative candour emerges:

"

Maybe the simplicity and directness [of my work] is intentionally against

a more hermetic work that has been the trend since the advent of conceptual

art. [My works] seem to have no secrets; we can see step by step how the thing

is made by looking at that process: by way of the finished painting."

No secrets, maybe, but still some enigma.